Main Menu

Welcome

As promised, find below the video of my talk at the Montreal Summer Institute on Consciousness. The abstract and some discussion can be found on the conference blog.

There is also a video of the subsequent panel discussion with all the speakers of that day (except Wolf Singer who could not attend the panel):

Posted on Sunday 08 July 2012 - 12:05:59 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

After an 11 hour odyssey at Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris, France, I'm finally back in Berlin. Unfortunately, I missed the first day of the symposium organized by our research unit on biogenic amines in insects due to the breakdown of flight control in Munich which caused my delay in Paris.

There is quite some discussion going on about my talk at the Montreal Summer Institute on Consciousness on the conference blog, maintained by organizer Stevan Harnad. The video of my presentation there is also online now, so go and have a look if you want to see what I talked about there. I still need to download it and put it on my YouTube channel.

Now I'm at the next conference, the symposium on biogenic amines in insects I mentioned above. This is really a great meeting with people all over the world talking about all kinds of insects and what biogenic amines do in the animals. Have a look at the program to get a glimpse at all the diverse topics we learn about here.

Posted on Saturday 07 July 2012 - 11:18:35 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

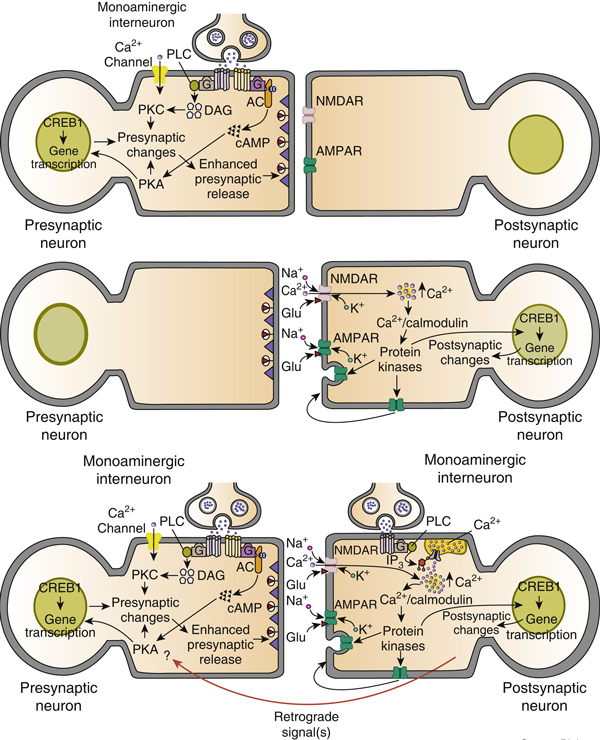

In his presentation on octpus consciousness at the Alan Turing Summer Institute on consciousness, David Edelman (son of Nobel Laureate Gerald Edelman) briefly referred to a paper by David Glanzman, showing a figure on synaptic plasticity that was merged from the three figures in David Glanzman's paper. I've reproduced this merged figure below, because I intend to use it in my lectures and I missed a figure like this one so far. It shows the transition towards a modern model of synaptic plasticity, with the topmost panel showing the 'invertebrate' presynaptic plasticity and then the 'vertebrate' postsynaptic plasticity as separate as they wre conceived up until about 1995. The final, lowermost panel shows the combined picture as both in invertebrates and in vertebrates there is sufficient evidence today pointing to both pre- and postsynaptic plasticity in all brains studied in enough detail so far:

This figure is a fusion of Figs. 1-3 from the Current Biology paper by David Glanzman linked to above.

Posted on Saturday 30 June 2012 - 21:52:15 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

At this great meeting in Montreal I won't have to blog a lot about each presentation, as most presentations will be videotaped and made available soon after. The first presentation (by Daniel Dennett) is already up can can be downloaded from organizer Stevan Harnad's program page. Just click on the "video" link behind each presentation to see what we are learning here.

All of the talks are of very high quality, interesting and highly educational, but from the first session, the one I chaired, I'd especially recommend the talks by Joseph LeDoux and Jorge Armony as particularly worth watching.

Posted on Saturday 30 June 2012 - 21:13:17 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

Yesterday was my last day of lectures in Leipzig (this week was on the genetics of cancer, sex determination and learning/memory in mice) and now I’m in Montréal attending lectures myself. I’m now at the Turing Centenary Institute on the Evolution and Function of Consciousness, slated to speak about our work on Thursday (see our program). The list of speakers is packed with luminaries like Daniel Dennett, Antonio Damasio, John Searle, Simon-Baron Cohen, Wolf Singer, Alfred Mele or Patrick Haggard, and the best thing is: you don’t have to be in Montreal with us to learn about the things we learn about – they will tape each lecture and put it online the next day (watch this space for the link).

What will this summer school be about? Here are some excerpts from their press release with some interjected statements of mine:

Alan Turing, born 100 years ago, invented the computer and computation and helped saved Europe by decoding Nazi message during World War I. He also proposed a simple way to test scientific explanations of how the mind works: the Turing test. If we can design a robot which is able to do anything and everything that a real human being can do – and can do it so well that people cannot even tell it apart from a real person, then we have explained how the mind works, and the robot has a mind. The challenge of passing the Turing test has created a new family of sciences called the cognitive sciences.

Hmm, I’m sure the discussion there will be interesting, as there are already a few things I wouldn’t necessarily agree with in this first paragraph. Only because a robot passes the Turing-Test, doesn’t mean it has a mind. Obviously, the definition of what constitutes a mind will be central for this discussion (and maybe a screening of “Blade Runner”, but alas, they will show other films):

But what does it mean to have a mind? Turing’s robot can do anything and everything we can do, but does that mean it has a mind? Could it not be a “Zombie,” that acts exactly the same way as we do, but it has no mind? What does it mean to have no mind? A rock has no mind. A waterfall has no mind. A toaster has no mind. And surely computers have no minds. What do all these mindless things lack?

They lack consciousness. What is consciousness? It is the ability to feel – to feel anything at all, whether it is a pinch, or a puff of air, or the sound of distant train, or the sight of a rainbow. If the robot that passed Turing’s test could not feel, it would not have a mind, even if it could do anything we can do, indistinguishably from us.

They lack consciousness. What is consciousness? It is the ability to feel – to feel anything at all, whether it is a pinch, or a puff of air, or the sound of distant train, or the sight of a rainbow. If the robot that passed Turing’s test could not feel, it would not have a mind, even if it could do anything we can do, indistinguishably from us.

Again, I’m not sure we can say with such certainty that consciousness is the only solution to the problem of behaving in a way that is indistinguishable from the way we behave. To me, there needs to be more than just a negative result of an experiment. There needs to be something that is as convincing as the brain we share with other human beings: it’s not just that we attribute consciousness to other people because we all behave the same. In fact, as individuals, we differ quite substantially from each other and still we attribute each other, by and large, conscious experiences. Part of this conviction is of course that all humans are alike: we have a brain that, in healthy humans at least, functions similarly. Thus, I think before I would go so far as to attribute consciousness to a robot, I’d want to see credible evidence not only that it behaves in a way that suggests consciousness, but in addition that it functions in a way that suggests conscious processes.

Of course, I’m well aware that as long as we don’t know how brains become conscious, this seems like an insurmountable obstacle.

This is the difference between doing and feeling. It is also called the mind/body problem. But what about the brain? Surely if we want to explain how the mind works the thing to study is not robots but the brain. Well, yes, but alas the brain does not reveal the secrets of its functioning as easily as a heart of kidney does. The brain can do what we can do, and measuring brain activity only tells us where and when things happen in the brain: not how and why the brain can do what it can do. And doing is Turing’s territory.

I’d also object to the notion that measuring brain activity cannot tell us how brains work. That may be correct if no other manipulations are performed, but even in these cases I wouldn’t exclude a mechanistic understanding from watching. However, observing brains in action in different, experimentally manipulated states does tell us quite a lot about the mechanistic processes taking place there.

What about feeling? The brain basis of consciousness is under intensive study by neuroscientists: How and why does the brain feel? This is the theme of the UQàM Summer Institute on the Evolution and Function of Consciousness: What function does feeling perform in the brain? What can be done with feeling that cannot be done with just doing? Feeling is a biological trait. What was the evolutionary advantage of feeling to our ancestors, what made those who felt survive and reproduce better, with the result that the ability to feel became encoded in our genetic material? Do lower animals feel – invertebrates, like snails or octopus, or even plants?

This is indeed a fascinating question: is consciousness really necessary for our survival and evolution, or was it an accidental by-product? I certainly don’t have an answer, but since consciousness is a brain function and neuronal activity is extremely expensive, my hunch is that consciousness is an adaptive function which was selected for.

And what about robots? What can they not do – what will they never be able to do – if they cannot feel? More challenging still: if a robot that can pass the Turing test does feel, what is the causal role of the feeling, in its internal functioning? All of us have the intuitive feeling that feeling has a causal role: I do what I do because I choose to do it. It feels as if my will is a kind of force. But is it? Whether we study the brain or we study robots, it always turns out that what either of them can do is fully explained by their internal functioning: There is no room for further causes. It is this role of consciousness as a causal force for which leading specialists from all over the world, and from all fields – brain science, computer science, robotics, evolutionary biology, psychology, and philosophy – are coming to Montreal for 12 days (June 29 – July 12) in a unique interaction one hundred years after the birth of the founder of both computer and the cognitive sciences.

I’m really very much looking forward to the next few days! Here’s a list with slated speakers and topics:

Mark Mitton: Mind & Magic

Turing Film 1: Code-Breaker

Turing Film 2: Le Modèle Turing (en français)

Turing Film 3: The Strange Life and Death of Dr. Turing

Turing Film 4: Alan Turing: Code-Breaker and AI Pioneer (Jack Copeland)

Daniel Dennett (Tufts) A Confusion About Access and Consciousness

Antonio Damasio (USC) Feelings and Sentience

Joseph Ledoux (NYU) Emotions and Consciousness

Jorge Armony (McGill) Neural Bases of Emotion

Fernando Cervero (McGill) Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Pain

Phillip Jackson (Laval) The Brain Response to the pain of Others

Catherine Tallon-Baudry (CNRS) Is Consciousness Executive Function?

Stevan Harnad (UQaM) Causal Role of Consciousness

Inman Harvey (Sussex, UK) Feelings: Why Would An Evolved Robot Care?

Ioannis Rekleitis (McGill) Basic Questions in Robotics

Dario Floreano (Lausanne, Switz.) Evolution Behavior in Robots

James Clark (McGill) Attention: Doing and Feeling

Michael Graziano (Princeton) Consciousness and the Attention Schema

John Campbell (Berkeley) Visual Experience

Patrick Haggard (UCL, UK) Volition: What is it For?

David Freedman (Cornell) Visual Categorization and Decision-Making

Shimon Edelman (Cornell) Being in Time

Wayne Sossin (McGill) Aplysia: Cellular Mechanisms of Sensation and Learning

Bernard Baars (NSI) Psycho-Biological Risks/Benefits of Consciousness

Ezequiel Morsella (SFSU) Primary Function of Consciousness in the Brain

Roy Baumeister (FSU) Why, What and How of Consciousness

Bjorn Merker (Sweden) Brain's Need for Sensory Consciousness

Paul Cisek (U Montreal) TDistributed Neural Mechanisms for Decision-Making

Michael Shadlen (HHMI) Consciousness as a Decision to Engage

Wolf Singer (MPI, Germany) Consciousness: Unity in Time Rather Than Space?

Erik Cook (McGill) Neural Fluctuations and Visual Perception

Björn Brembs (FU Berlin, Germany) Evolutionary precursors of "Free Will" in flies

Julio Martinez (McGill) Attention Memory Primates

Christopher Pack (McGill) Vision During Unconsciousness

Barbara Finlay (Cornell) Brain Evolution and Cognitive Capacities

Gary Comstock (NCSU) Feeling Matters

David Rosenthal (CUNY Grad) Does Consciousness Have any Utility?

Mark Balaguer (Cal State) Indeterministic Libertarian Free Will

Adrian Ward (Harvard) Mind Blanking

Simon Baron-Cohen (Cambridge UK) Evolution of Empathy

Alfred Mele (FSU) Conscious Decisions and Action

Hakwan Lau (Columbia) Functions of awareness

Luiz Pessoa (U Maryland) Cognitive-Emotional Interactions

Marthe Kiley-Worthington (EEREC, France) Elephant and Equine Consciousness

Axel Cleermans (ULB, Belgium) Consciousness and Learning

Stefano Mancuso (LINV, Italy) Evolution of Plant Intelligence

Gualtiero Piccinini (UMO, St Louis) Is Consciousness a Spandrel?

Malcolm MacIver (Lethbridge) Emergence of Multiple Futures

Jennifer Mather (Lethbridge) Evolution of Cephalopod Consciousness

Eva Jablonka (TAU, Israel) Evolutionary Origins of Experiencing

Alain Ptito (McGill) Blindsight after Hemispherectomy

Amir Shmuel (McGill) Measuring brain activity and connectivity

Gilles Plourde (McGill) General Anesthetics for the Study Consciousness

Amir Raz (McGill) Hypnosis to Study Metacognition, Causality and Volition

John Searle (Berkeley) Consciousness and Causality

Workshops:

Functional connectivity using neuroimaging (organizer: Sarah Lippe, U. Montreal)

Transcranial stimulation (organizer: Hugo Theoret, U. Montreal)

Magnetoencephalography (2) (organizers: Sylvain Baillet, U McGill & Pierre Jolicoeur, U Montreal)

Informational correlates of consciousness using Bubbles (organizer: Frederic Gosselin, U Montreal)

Posted on Saturday 30 June 2012 - 12:54:00 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

I've written a few times already about why I think (university) libraries are in a perfect position to take over scholarly communication from corporate publishers. Among other things I've mentioned that they already publish many of our theses, ancient texts and host journal article repositories (although it is of course clear that at the moment "repositories are failures – most have at best a few per cent of their output and academics either ignore them or regard them as a distraction or impediment. No-one uses them to discover scientific information because they are disorganised, have no useful search tools, and do not interoperate" this is easily fixable). Any such transition could be easily funded by the billions saved anually if subscriptions were cut. Given current publisher profit margins, the projected annual savings, once the transition is complete, would be about 4 billion (EUR/USD) every year - that's not exactly pocket change.

In two comments on the recent posts, both David Crotty and Neil Stewert pointed out that, in addition to the expertise I've already listed, (some) libraries already have all the tools, knowledge and training for proper academic publishing. The two examples the commenters mentioned (I'm now sure there are many more) were SAS Open Journals and Highwire Press. Thus, all it takes to transition from a system in which we outsource publishing to commercial publishers and lose approx. 40% of the money we pay to their shareholders to one where we get to keep these 40% to innovate and develop a modern scholarly communication system, is to cut subscriptions to free funds for disseminating the know-how and the technology, as well as for extending the available infrastructure to make the different libraries interoperable according to a global standard (of course by hiring a bunch of smart experts, preferably from corporate publishers).

The more I learn, the more realistic it sounds to me that I actually might live to see a scholarly communication system that's not totally FUBAR.

Posted on Friday 22 June 2012 - 14:52:31 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

In the UK, the recent "Finch Report" on Open Access has generated a shower of online commentary both from the mainstream media and from activists. I've only linked to a few recent one's to outline the current discussion on how to best move towards universal Open Access to taxpayer-funded research results. The most important (and maybe also most predictable) piece of information is a change in strategy by the commercial publishers. After the recent RWA debacle, the ensuing Cost of Knowledge coverage and the successful petition to the US White House for open access, it appears as if the commercial publishers have conceded defeat and now accept that their subscription model is not supported anymore.

That's a clear win for the Open Access movement and should be celebrated.

The Finch report, however, as pointed out by early commenters, shows clear signs of publishing industry lobbying in emphasizing that the main strategy towards OA should be via journals (read: published by commercial publishers). The way I read it, the new strategy of the commercial publishers is to delay the transition towards OA for as long as possible and charge as much as possible for it, complemented by threats of job loss (see response). Given the utter defeat in their previous tactics, this stalling and harassment strategy is a reasonable fall-back position for the publishing industry and, given their deep pockets, one that could, in principle, work for at least another decade or two.

I've pointed out before that I have yet to hear any convincing arguments for why we should outsource scholarly communication to commercial entities to begin with. (University) libraries are perfectly capable of providing better services to the scholarly community, at a lower cost, than corporate publishers. Apparently, as recently pointed out, the commercial publishers also agree that they provide little added value, or they would not lobby so hard for their commercial journals to provide these services, instead of libraries - this is the 'green' vs. 'gold' debate in the struggle for the best way to universal Open Access. Now, publishers push for 'Gold OA', i.e. to secure their market via lobbying for industry-friendly legislation/policy, while the OA movement is still divided and debates the respective values of gold vs. green. To me, the data that is starting to come in that a hierarchy of journals in general is bad for science, together with the unreasonable profits by commercial publishers off of taxpayer funds (i.e. subsidies), I see a library-based, modern, hi-tech, IT-assisted scholarly communication system as a win/win/win strategy: less counter-productive incentives due to a article-based assessment system, less costly and benefiting science.

The question thus arises, how to convince politicians and administrators at funding agencies that corporate publishers do not have science, but profit at their core interest? Stevan Harnad has been arguing for the longest time for green OA (I agree in principle, but disagree quite strongly on some significant specifics). If these Tweets are any indication, the way Stevan argues, may not be very effective:

Due to the brevity of Twitter, it wasn't reasonable to ask or argue with Stephen Curry what exactly he meant, but I can only guess that he felt politicians won't be persuaded by Stevan's arguments, at least not the way he put them. So how do we best convey the message that commercial publishing of scientific papers is the dinosaur in scholarly communication? How do we effectively communicate that around four billion (EUR, USD) could be saved annually if libraries were instead hosting our communications in a modern, effective and technically savvy way? How do we let them know that peer-review is not an issue and that jobs most likely will be created rather than lost? How can we most effectively communicate that further subsidy of a dead industry is not in the interest of the taxpayer?

Posted on Thursday 21 June 2012 - 11:32:45 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

Four months after the last spam campaign by Nature magazine, I find more spam mail from Nature Publishing Group in my JunkMail folder. Here they go again, touting their Impact Factor to the third decimal (more scientifical that way!) and proclaiming whopping 15% and 11% leads ahead of Science and Cell, respectively. Importantly, if I were to subscribe to their content (which I either get for free online, if it's news or I already paid for as a taxpayer, if it's research papers), I'd get a 60% discount. Boy, do they desperately need to sell their dead trees:

http://hosted.verticalresponse.com/510441/c336a5e592/1702575377/911d6fdd38

And it's not like they wouldn't know that Thomson Reuter's 'Impact Factor'

- is negotiable and doesn't reflect actual citation counts (source1, source2)

- cannot be reproduced, even if it reflected actual citations (source)

- is not statistically sound, even if it were reproducible and reflected actual citations (source)

If it helps making money, any and all scientific considerations are thrown under the bus. Perhaps not coincidentally, these campaigns started around the time when the data started showing that the IF predicts the unreliability of research papers, undermining the credibility and trustworthiness of journals such as Nature.

What can I say, 'world class' indeed

Posted on Tuesday 19 June 2012 - 09:46:09 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

While quantum physics teaches us that predicting the future is impossible, forecasting it is possible but fraught with errors, uncertainties and it is exceedingly difficult. Our own research tells us that our ability to forecast the behavior of animals and humans decreases with the amount of time into the future I want to forecast the behavior. However, there are some extreme cases where behaviors are exceedingly easy to predict. Faced with this situation, most people will turn and run:

Over the last few weeks and months, we've seen comments and articles from corporate academic publishers that make their customers turn and run about as predictably as this charging lion would. A recent release from Springer topped this all off with insulting/threatening a scientist (i.e., Springer customer) when he alerted them to their own mistakes and possible transgressions. A friend, who is also an academic publisher, asked me what he could do to not be lumped in with the corporate publishers and be tainted by their image sure to erode their (and potentially his) customer base.

I answered that, from a scientist's perspective, he should try and follow three easy rules, which wouldn't ensure staying in business, but at least would help prevent alienating his customers:

- Don't insult or threaten your customers. If, for instance, they complain about your mistakes, apologize and promise to not make that mistake again.

- Don't charge your customers so much that you make profits which would make Steve Jobs rotate in his grave in envy. Like people looking into Apple's business practices in China, people will start checking where these profits come from, if they're seen as too excessive. That's the case for any business, but especially so if the money you're charging comes from tax-payers who weren't asked if they want to line your shareholders' pockets with their hard-earned cash.

- Finally and perhaps most importantly: Make sure you have a good case for charging the money you charge. If you try to prevent publication of the part of the work you didn't add your value to (i.e., the preprints of the scientists who submitted their work to you), you send the unmistakable message that you find your contribution to scholarly communication to be so worthless, that nobody would pay anything for it and that you expect people to rather read the work without your added value, than pay for your added value. In other words, believe in your product yourself before you try to sell it.

Heeding these three simple rules won't guarantee you stay in business, but violating them will almost certainly guarantee you'll be out of business soon - with about the same certainty with which one could predict that anybody would turn and run from a charging lion.

Posted on Thursday 07 June 2012 - 14:37:41 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

There is a petition out in the US asking the Obama administration for an executive order mandating "free, timely access over the Internet to journal articles arising from taxpayer-funded research". Anyone can sign the petition, not just those based in the US. Here is the text of the petition:

WE PETITION THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION TO:

Require free, timely access over the Internet to journal articles arising from taxpayer-funded research.

We believe in the power of the Internet to foster innovation, research, and education. Requiring the published results of taxpayer-funded research to be posted on the Internet in human and machine readable form would provide access to patients and caregivers, students and their teachers, researchers, entrepreneurs, and other taxpayers who paid for the research. Expanding access would speed the research process and increase the return on our investment in scientific research.

The highly successful Public Access Policy of the National Institutes of Health proves that this can be done without disrupting the research process, and we urge President Obama to act now to implement open access policies for all federal agencies that fund scientific research.

The effort is aimed towards the "We The People" web platform to petition the White House directly. We have 30 days to reach 25,000 signatures, so every day and every signature counts. Given the 11k signatures on the Elsevier boycott and the roughly 30k on the Open Access pledges for support ten years ago, this is a very realistic scenario and if succesfull would require the Obama administration to publicly respond to the petition.Require free, timely access over the Internet to journal articles arising from taxpayer-funded research.

We believe in the power of the Internet to foster innovation, research, and education. Requiring the published results of taxpayer-funded research to be posted on the Internet in human and machine readable form would provide access to patients and caregivers, students and their teachers, researchers, entrepreneurs, and other taxpayers who paid for the research. Expanding access would speed the research process and increase the return on our investment in scientific research.

The highly successful Public Access Policy of the National Institutes of Health proves that this can be done without disrupting the research process, and we urge President Obama to act now to implement open access policies for all federal agencies that fund scientific research.

The goal is to reach beyond academia and get as many people as possible to sign the petition to show that Open Access is important for everyone. So what are you waiting for? Go ask you sister, brother, aunt, uncle, mother, father as well as all and any other relatives and friends you have to go and sign this important petition! The official campaign website is at http://access2research.org and there is a Facebook page and a Twitter handle (@access2research) in place. So go and sign the petition, become a fan on Facebook, follow and retweet on Twitter as much as you can for the coming 30 days to get the petition over 25,000 signatures. For today, the Twitter hashtag is #OAMonday.

Posted on Monday 21 May 2012 - 10:13:58 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

Render time: 0.2664 sec, 0.0097 of that for queries.