Main Menu

Welcome

In what might become a review article, I've recently been collecting published data about Thomson Reuters' Impact Factor (IF). So far, this data suggests that the IF predicts retractions better than it predicts citations and that this, in part, appears to be due to less reliable research being published in high-IF journals. At the moment, we lack the data to understand more about these relationships, but it may be that what has been termed the 'decline effect' might at least in part be due to journal rank as defined by IF. Journal rank, of course, being vital for a researcher's livelihood: no papers in high-IF journals usually means burger-flipping becoming a lucrative career option for a senior postdoc. The idea behind this way of deciding about the careers of scientists is straightforward: high-IF journals publish high-quality research and if you don't publish high quality research you should be looking for another job.

But not only for scientists is the IF a vital number. Journals survive on subscription fees than can be as high as several tens of thousands of Euros/dollars per year. When deciding which journals to subscribe to, libraries often look at the IF of the journals. The idea being that high-IF journals publish high-quality research and thus should be available for the faculty (as opposed to the low-IF/low-quality journals). Thus, just as scientists might not necessarily submit their 'best' work to high-IF journals, but rather their 'splashiest' manuscripts, i.e., the ones with the most surprising results, journals have an incentive to increase their IF as well: the higher the IF, the higher the number of subscriptions.

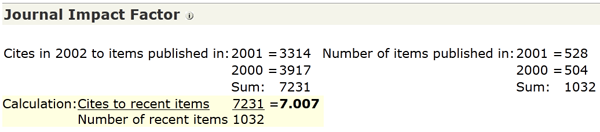

The way Thomson Reuters comes up with the IF makes it particularly easy for journals to increase their IF: publishers have the possibility to negotiate how their IF is calculated. In the case of PLoS Medicine, the negotiation range was between 2 and about 11. However, these negotiations take place behind closed doors and so we only rarely become aware of them. A few years ago, triggered by a reference in an article, I went to the Journal Citation Reports (subscription required) website of Thomson Reuters and looked up the IFs of the journal Current Biology in 2002 and 2003, the two IFs following the purchase of Current Biology by Cell Press (owned by Elsevier). You can have a look the screenshots with all the relevant data for 2002 and 2003, but I've zoomed into the relevant parts below:

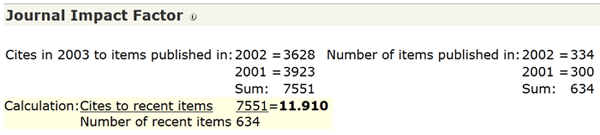

You can see how Thomson calculates the IF for 2002: number of citations in the current year to papers in the preceding two years, divided by the number of 'citable items' in these years. Because of the IF covering two years, the next IF, that from 2003, overlaps with the previous one in some of the data from 2001. Clearly, the information about what was published should be identical: 528 papers in 2001. Now let's see if this is what we find in the 2003 JCR:

Interestingly, while the number of citations has remained roughly constant from one year to the next, the number of papers published dropped from 528 to only 300. Consequently, Current Biology's IF jumped from 7 to almost 12, supporting the description in the PLoS Medicine editorial about the negotiations taking place between publishers and Thomson Reuters. It is difficult to imagine how sometime in 2002, several hundred published papers somehow got lost in the Thomson Reuters database. Why is it even possible to enter two different values for the same year? It is also difficult to believe that this adjustment happened just coincidentally immediately after Current Biology was bought by the publisher with the deepest pockets, annually netting profits in the hundreds of millions. It is rather telling that Thomson did not even chose to wait for a year to avoid at least the impression of manipulations.

It continues to be an embarrassment for science that we rely on such a blatantly anti-scientific number for our hire-and-fire decisions and it spells trouble for the generation of scientists who are to come of this system. Maybe the 'year of retractions' in 2011 will be the new normal?

Posted on Tuesday 03 January 2012 - 19:17:42 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

You must be logged in to make comments on this site - please log in, or if you are not registered click here to signup

Render time: 0.0951 sec, 0.0067 of that for queries.