Main Menu

Welcome

In science, journals publishing scholarly articles are ranked by a multi-billion dollar corporation (Thomson Reuters, TR) according to very opaque, unscientific methods. Of course, this corporation sells their ranking to scientific institutions for huge profits. My own university just told us yesterday that they are proud to now be able to afford this service starting next year.

But back to the scientists asking publishers or TR which scientific articles they should read. I would tend to believe that even these scientists, like all ordinary people, would either ask friends or consult newspapers or magazines, or even, gasp, the internet, for advice on where to eat, which concert is worth attending or if the new blockbuster is going to be worth spending a date on. Most likely, they would not take statements by the restaurant owner, or the band manager or the movie producer very seriously. These persons would have a rather obvious conflict of interest. However, it seems perfectly fine for these scientists to take professional editors at high ranking journals seriously, when they tell them they should read the articles they are selling in their own journal. How bizarre is that?

People use Guide Michelin because their staff actually taste the food in the restaurants. People use movie or concert reviews because the authors have actually seen the movie, been to the concert. It would seem very bizarre indeed if one would choose the concert exclusively because that particular venue had great concerts before. It would also seem bizarre if one would choose a restaurant because that particular street happens to have a good restaurant a few blocks down. Most people would probably also find it bizarre if people chose to see a particular movie only because of the movie studio it was shot in.

And yet, this is precisely what happens in science.

One reason it happens is that it is rare to find independent reviews of recently published papers. Most of these reviews are commissioned by the publisher and will understandably be fluff pieces. If anything, reading such a news piece on a scientific publication would often enough do the opposite and prevent scientists from actually reading the paper itself: they now already know its content, by and large. However, even if these pieces weren't commissioned and at least technically 'independent', you would still be hard pressed to find candid negative reviews as it's usually scientists writing about other scientists. F1000 Prime provides such an independent platform (in which I participate as a volunteer faculty member), but it is only set up for positive evaluations. Another thing that might seem quite bizarre from a non-scientist perspective: a culture of critical, investigative science journalism is only just now evolving.

However, the vast, vast majority of articles never receive any such coverage at all. Thus, in the absence of even fluff coverage, what is a researcher to do? In this case, he or she is in the same boat as someone looking for music, movies or restaurants: just like there isn't an objective measure for the best music, the best movie or the best food, there isn't an objective measure for the best science. So, since TR provides the veneer of something objective, scientists routinely use something that has been shown time and again to be unscientific, to the embarrassment of all other scientists. Just yesterday, at our faculty council meeting, one colleague mentioned the journals where a candidate had published as credentials of his/her excellence. Just as if the street where a restaurant is located, would tell anything about the quality of their food, or the record label would tell anything about the 'quality' of the music.

Some organizations have recently sprung up to remedy this, though: they collect data on various aspects of article impact irrespective of journal. One common criticism of such article level metrics is that the metrics have to accrue over time, while journal rank tells you immediately which articles are worth reading. Which is the last bizarre thing I'll write about today: how do you know which is the best music out of the music nobody has listened to, yet? How can you tell which is the best movie of those nobody has seen, yet? How do you figure out which is the best restaurant, of those where nobody has eaten, yet? For anything but science, the answer is obvious.

Posted on Thursday 15 November 2012 - 13:22:42 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

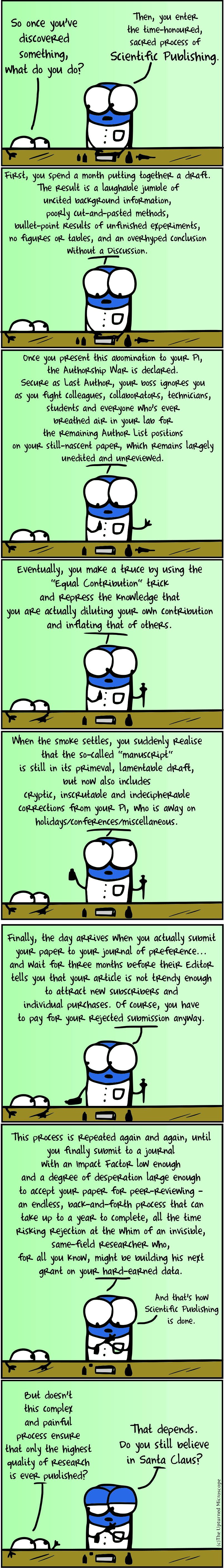

Just saw this at breakfast and need to spread it (via @caseybergman, originally from The Upturned Microscope):

Posted on Thursday 15 November 2012 - 10:21:43 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

As a strong supporter of any open access initative over the last almost ten years, there is now a looming threat that the situation may deteriorate beyond the abysmal state scholarly publishing is in right now.

Yes, you read that right: it can get worse than it is today.

What would be worse? Universal gold open access - that is, every publisher charges the authors what they want for making the articles publicly accessible. I've been privately warning of this danger for some time, and now an email and a blog post by Ross Mounce reminded me that it is about time to make my lingering fear a little more public. He wrote:

What is so surprising about charging for nothing? That's been the modus operandi of publishers since the advent of the internet.

Why should NPG not charge, say, 20k USD for an OA article in Nature, if they chose to do so?

If people are willing to pay more than 230k ($58,600 a year) for a Yale degree or over 250k ($62,772 a year) just to have "Harvard" on their diplomas, why wouldn't they be willing to shell out a meager 20k for a paper that might give them tenure? That's just a drop in the bucket, pocket cash.

I'd even be willing to bet that the hard limit for gold OA luxury segment publishing will be closer to 50k or even higher as multiple authors can share the cost. Without regulation, publishers can charge whatever the market is willing and able to pay. If a Nature paper is required, people will pay what it takes.

If libraries let themselves be extorted by publishers out of fear they'll get yelled at by their faculty, surely

scientists will let themselves get extorted by publishers out of fear they won't be able to put food on the table nor pay the rent without the next grant/position.

Who seriously believes that only because they now make some articles OA, publishers would all of a sudden become non-profit organisations?

I don't see anything extraordinary in this press release at all, completely normal and very much expected. In fact, the price difference is actually quite small.

I really have no idea what's supposed to be so outrageous about this?

Obviously, the alternative to gold OA cannot be a subscription model. I've written repeatedly that I believe a rational solution would be to have libraries archive and make accessible the fruits of our labor: publications, data and software. There can be a thriving marketplace of services around these academic crown jewels, but the booty stays in-house.

At the very least, if there ever should be universal gold OA, the market needs to be heavily regulated with drastic price caps below current author processing charges, or the situation will be worse than today: today, you have to cozy up with professional editors to get published in 'luxury segment' journals. In a universal OA world, you would also have to be rich. This may be better for the public in the short term, a they then would at least be able to access all the research. In the long term, however, if science suffers, so will eventually the public.

Every market I know has a luxury segment. I'll gladly rest my fears if someone shows me a market without such a segment and how it is similar to a universal OA academic publishing market. Unitl then, I'll be working towards getting rid of publishers and journal rank.

Yes, you read that right: it can get worse than it is today.

What would be worse? Universal gold open access - that is, every publisher charges the authors what they want for making the articles publicly accessible. I've been privately warning of this danger for some time, and now an email and a blog post by Ross Mounce reminded me that it is about time to make my lingering fear a little more public. He wrote:

Outrageous press release from Nature Publishing Group today.

They're explicitly charging more to authors who want CC BY Gold OA, relative to more restrictive licenses such as CC BY-NC-SA. Here's my quick take on it:

http://rossmounce.co.uk/2012/11/07/gold-oa-pricewatch

More money, for absolutely no extra work.

How is that different from what these publishers have been doing all these years and still are doing today?They're explicitly charging more to authors who want CC BY Gold OA, relative to more restrictive licenses such as CC BY-NC-SA. Here's my quick take on it:

http://rossmounce.co.uk/2012/11/07/gold-oa-pricewatch

More money, for absolutely no extra work.

What is so surprising about charging for nothing? That's been the modus operandi of publishers since the advent of the internet.

Why should NPG not charge, say, 20k USD for an OA article in Nature, if they chose to do so?

If people are willing to pay more than 230k ($58,600 a year) for a Yale degree or over 250k ($62,772 a year) just to have "Harvard" on their diplomas, why wouldn't they be willing to shell out a meager 20k for a paper that might give them tenure? That's just a drop in the bucket, pocket cash.

I'd even be willing to bet that the hard limit for gold OA luxury segment publishing will be closer to 50k or even higher as multiple authors can share the cost. Without regulation, publishers can charge whatever the market is willing and able to pay. If a Nature paper is required, people will pay what it takes.

If libraries let themselves be extorted by publishers out of fear they'll get yelled at by their faculty, surely

scientists will let themselves get extorted by publishers out of fear they won't be able to put food on the table nor pay the rent without the next grant/position.

Who seriously believes that only because they now make some articles OA, publishers would all of a sudden become non-profit organisations?

I don't see anything extraordinary in this press release at all, completely normal and very much expected. In fact, the price difference is actually quite small.

I really have no idea what's supposed to be so outrageous about this?

Obviously, the alternative to gold OA cannot be a subscription model. I've written repeatedly that I believe a rational solution would be to have libraries archive and make accessible the fruits of our labor: publications, data and software. There can be a thriving marketplace of services around these academic crown jewels, but the booty stays in-house.

At the very least, if there ever should be universal gold OA, the market needs to be heavily regulated with drastic price caps below current author processing charges, or the situation will be worse than today: today, you have to cozy up with professional editors to get published in 'luxury segment' journals. In a universal OA world, you would also have to be rich. This may be better for the public in the short term, a they then would at least be able to access all the research. In the long term, however, if science suffers, so will eventually the public.

Every market I know has a luxury segment. I'll gladly rest my fears if someone shows me a market without such a segment and how it is similar to a universal OA academic publishing market. Unitl then, I'll be working towards getting rid of publishers and journal rank.

Posted on Wednesday 07 November 2012 - 23:04:14 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

After an unusually rewarding and exciting SfN meeting in New Orleans with many ideas and new tools for the next experiments, I spent a day at my old lab in Houston, Texas to record some new, higher resolution videos of spontaneous biting in the marine snail Aplysia:

The day after I drove down to Texas A&M at Corpus Christi to visit my good friends Riccardo Mozzachiodi and his wife Marcy. They want to start the same kinds of recordings in Aplysia I did during my time in Houston, so we sat down and went through the technical details of recording from live, intact Aplysia snails. Conveniently, there is a JoVE video from another good friend, Hillel Chiel who pioneered this work. The technique I used was very similar to the one shown in this video (no embedding code available).

Finally, I flew to Sydney via Los Angeles to participate in a workshop on invertebrate cognition. The first speaker on the first day ("show and tell") was Max Coltheart describing his work on humans, including accounts of some very weird delusional patients. He was followed by another good friend, Martin Giurfa, who presented many different examples of components of cognition in insects. Third speaker was Sue Healy who talked about comparative cognition in vertebrate species. Next on was Jeremy Niven who talked about various examples of complex behavior in more and more miniaturized brains and their increasingly weird and exciting neurophysiology.

And now it's time for lunch and at 3pm I'm up with my talk so I don't expect to be blogging any more until tomorrow.

Posted on Tuesday 23 October 2012 - 03:07:17 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

A recent flurry of posts and discussions prompted me to summarize a connected set of issues that I haven't really seen covered simultaneously elsewhere. I don't doubt everyone's aware of the issues, I just haven't seen anyone make the case that all the following three issues are related and, ultimately, have the same cause and thus, the same potential solution.

The astonishing gall with which corporate publishers strangle research and teaching institutions worldwide, even in the face of drastic cuts to said institutions budget is not a white gauntlet but a fist in the face of every taxpayer, paired with a big, raised middle finger. And yet, little is happening to make sure not more tax funds are being siphoned into the pockets of corporate CEOs and their shareholders. As outrageous and infuriating as such corporate behavior is, it is but merely a symptom of a wider infrastructure crisis in the sciences we have brought upon ourselves. Two factors have critically contributed to this crisis:

- We outsourced the dissemination of our products to publishers

- In the course of #1, we have ceased to see our libraries as the obvious custodians of said products.

What are the products libraries are supposed to be the custodians of?

To answer this question, one only needs to look at what we do. Experimental science (and the following will be, of course, different in different fields) generally proceeds today in three main steps:

- Experiments generate raw data

- Software helps evaluate the data

- The evaluated data is presented to the scientific community in a publication

To my knowledge, there is no central place where one can efficiently search for scientific software. We have deposited our software for a recent project on sourceforge. This site contains both the software for data acquisition and for evaluation. I imagine many other colleagues post their software on similar sites, if they make their software available at all. Why is it not the most natural and obvious thing to store our software with our institutions? If we wouldn't donate billions every year to publishers, we would have more than enough funds to run all software repositories many times over. On top of that, we'd be able to continuously modernize and update the resulting infrastructure.

To me, publishing is the most annoying component of my work. In fact, it's the deep frustration and anger associated with publishing our work which fuels my motivation to try and contribute at least a little to publishing reform. Why is it not the most natural and obvious thing to store our publications with our institutions? If we wouldn't donate billions every year to publishers, we would have more than enough funds to run all journals on this planet and have plenty of funds left for data and software repositories. On top of that, we'd be able to continuously modernize and update the resulting infrastructure and incorporate links between data, software and literature, such that one could, for instance click on a figure in a paper, specify different parameters and visualize the data differently than the authors did. This is technically trivial today and used, e.g. on the website of Reed Elsevier to visualize their financial developments. Why does Reed Elsevier use this technology on their website, but we can't use it in our publications?

On top of the infrastructure crisis we face with our dysfunctional publication system, we also face two more crises, those of data and software. Tragically, by outsourcing not just the service of publishing, but simultaneously also the rights to our products, we have paved the way for the two more modern crises. We don't see libraries as the obvious place for our products any more and this has proved to be a pernicious development. It is time we bring the fruits of our labor back into our control and create a thriving market for services around our products. All of our products have been funded by the taxpayer and must be freely accessible and re-usable for every taxpayer. It is of course more than just ethically justifiable to spend tax funds to increase the efficiency of this dissemination and re-use, specifically if the market is healthy and competitive. But the fruits of our labor themselves need to be fully under our own control and not under that of for-profit corporations, often with diametrically opposed interests from the general public that supported our work to begin with.

The general gist of this post was presented in my keynote address at this year's open access days in Vienna, Austria:

Apparently, Slideshare doesn't offer old embed codes any more...

Posted on Thursday 18 October 2012 - 21:28:48 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

Believe it or not, this year we actually have our posters ready a full day before we have to leave for SfN! That they are posted here also a day before we fly off to New Orleans, must be a first - and this is my 12th SfN conference!

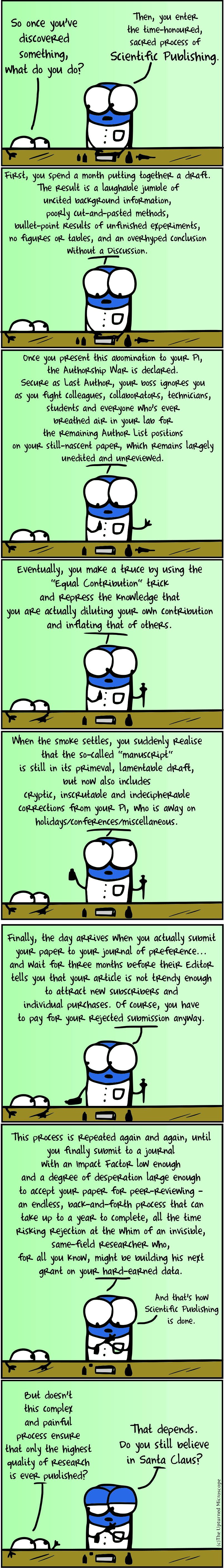

Our graduate student Christine Damrau will present her work Monday on the roles of octopamine in walking and sucrose preference:

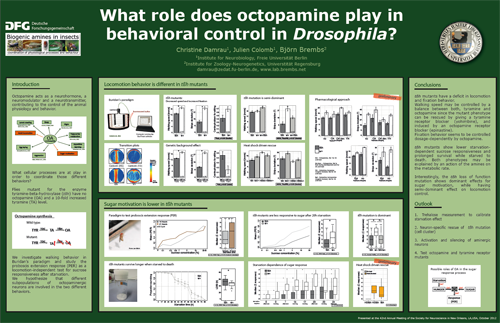

I'll be presenting the second poster Tuesday morning on the identification and localization of Protein Kinase C in self-learning:

I'm currently using the über-cool Hubbian to chose the posters I want to see this year. Maybe I won't need to use SfN's meeting planner any more?

Posted on Thursday 11 October 2012 - 00:25:54 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

As I wrote, the last two weeks were mainly filled with relocating from Berlin to Regensburg. As in Germany only 13% of all those employed in research and teaching have permanent positions, offers of tenured professorships don't come often and I seized the opportunity, even though I really felt at home in Berlin these last nine years. Starting October 1 I'll be joining the ranks of approximately 25k university professors in Germany and you can have a look at the diploma they hand you on that occasion below:

I received this diploma just over two hours ago and the president of the university actually had a little bottle of champaign in his office for the occasion - at 9am...

Tenure (at least the German version of it) opens up a whole new range of possibilities. Now I can finally begin those infrastructure projects I was never able to tackle: I can now try to replicate the machine I use for my experiments such that I can multiply my experimental output. I can start thinking about a coherent software infrastructure that allows all experiments to generate interoperable data structures, such that all our data can be deposited in realtime in online databases for archiving and sharing. In brief, all those long-term projects which are impossible on fixed contracts with the pressure to publish continuously.

Now is the time to do science the way it ought to be done, which is impossible without tenure. I'm looking forward to that, after about 17 years in the business.

Posted on Wednesday 19 September 2012 - 11:41:08 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

I haven't been able to post much recently as I was busy packing and unpacking boxes. It is not without sadness that I must announce my departure from Berlin. I will be visiting Berlin tomorrow and Friday but after that I'll be living and working in Regensburg in Bavaria as a tenured professor in the Zoology department of the university there (nevermind their outdated page - it'll show a link to my lab eventually). Below you can see how our daughter Freya instructs Jörn Kaspar on the moving van as to where to put her stuff:

My new addres there will be:

Prof. Dr. Björn Brembs

Institute of Zoology

Universitätsstr. 31

Universität Regensburg

93040 Regensburg

Just in case someone would like to send me a package or something

Posted on Wednesday 19 September 2012 - 11:18:03 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

Today, I came across two very different but equally interesting and telling things to read. One was a letter from our funding agency ( DFG) explaining why our main grant wasn't renewed and one was this article on the evaluation of science. The reasons for the grant rejection were quite easy: both reviewers complained that the results from the one project in the grant which we didn't want to renew was not described in the renewal application. Wouldn't have occurred to me that this should be in there. The other reason both reviewers raised was that we hadn't presented sufficient publications or publication-ready data, despite the fact that one crucial machine was broken for one out of the 2.5 years of the preceding grant period.

I'm not sure what to make of the first comment, but the second comment made me think that if I ever publish more than 0.5-1 papers a year out of one project, the questions I'm asking have become too easy to answer. Clearly, putting out a lot of papers is not a sign of better science. In fact, it seems more like an indication of the opposite to me.

The article above containing the eloquent and passionate plea to change the way we do science joins a long list of similar articles that are being written over the years in virtually every scientific journal and yet, the way we evaluate science has become worse and worse for the last two decades. Obviously, appealing to honor or professional standards is not an effective way to actually bring about change, at least not in the scientific community. Maybe what is needed is hard, solid evidence? The kind of evidence that convinces scientists in their everyday jobs. This idea prompted Marcus Munafó and me to write a review paper on the empirical evidence about the relation of journal rank to various measures of scientific impact or quality. We have recently published a draft of this manuscriptwhich we are currently revising. Our review arrives at the following four conclusions:

- Journal rank is a weak to moderate predictor of scientific impact;

- Journal rank is a moderate to strong predictor of both intentional and unintentional scientific unreliability;

- Journal rank is expensive, delays science and frustrates researchers;

- Journal rank as established by Thomson Reuters' Impact Factor violates even the most basic scientific standards, but predicts subjective judgments of journal quality.

Looking at the literature, it becomes clear that the only reasonable way to decide about the value of a scientific project, paper or scientist is to understand it. For instance, you can't take the number of papers of a person and conclude that they make difficult problems look easy because they've published many papers - the problems may, in fact, have been easy. These sorts of reflections hold for any kind of metric. However, the scientific enterprise has become so large and diverse that it is practically impossible to understand all the problems, scientists and proposals one has to evaluate - both in terms of number and in terms of diversity. Is the consequential solution then to shrink science - maybe a particularly attractive option given current international budget crises? While this would eventually solve the problem of having too many scientific entities to evaluate, it would not solve the problem of diversity: metrics would still be required to be able to at least get a rough understanding of the relative merit of work that is just to far from one's own area of expertise to ever be able to understand at sufficient detail.

Thus, I think the rational solution is to begrudgingly accept that metrics will be required for scientific evaluation in the future. This requirement entails that we all become thoroughly familiar with their use and misuse, with the incentives they provide and that we use them prudently and with scientific rigor. Anything else would not only be irresponsible, it would also be short-sighted and eventually self-defeating.

Posted on Friday 31 August 2012 - 16:56:45 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

UPDATE: The piece in Nature is not, as I initially thought, a new article. It was already published in 2004, but for reasons only "the no. 1 weekly science journal" knows, it always has today's date attached to it and prominently displayed. While the arguments are thus outdated, they were already wrong in 2004.

Hot on the heels of confusing science with religion, the journal that calls itself "the no. 1 weekly science journal" (Nature) goes on to embarrass itself with "an independent assessment of the key arguments" surrounding open access. Given that Nature Publishing Group is a stakeholder itself, the independence of anything published there should not be taken for granted. Let's have a look at some of these 'independent arguments':

But even where research is publicly-funded, taxes are generally not paid so that taxpayers can access research results, but rather so that society can benefit from the results of that research; in the form of new medical treatments, for example. Publishers claim that 90% of potential readers can access 90% of all available content through national or research libraries, and while this may not be as easy as accessing an article online directly it is certainly possible.

In other words, society doesn't benefit from doctors and patients having access to medical research? That retired professors have access to research? The list goes on, e.g. at whoneedsaccess.org. Clearly, not even close to 90% of those who need access have access to even anything remotely close to 90%. How about some survey data to counter baseless publishers' assertions who has access to how much? See slide 35 of my presentation. I'd challenge the publishers to back their claim up with some data, preferentially not their own surveys, if they have done any.Another criticism of open access is that payment for publication could create conflicts of interest and have a negative impact on the perceived neutrality of peer review, as there would be a financial incentive for journals to publish more articles.

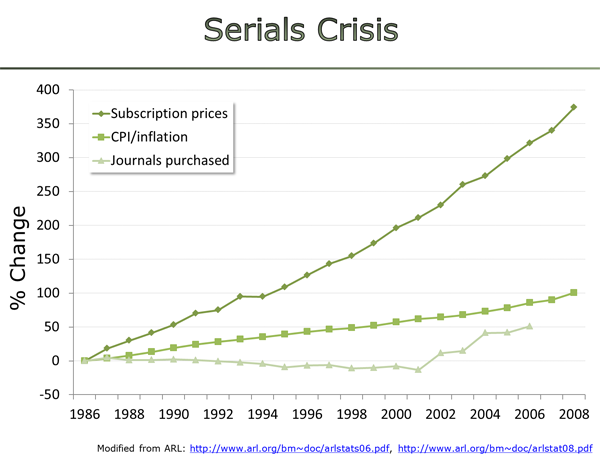

That argument only holds if one follows the baseless assumption that we should keep a journal system based on corporate publishers. Because corporate publishers in scholarly communication have about as much justification for their existence as the Pony Express or the telegraph, all arguments resting on that assumption fall flat. As previously pointed out on this blog and elsewhere, libraries (i.e. the ones paying the publishers) are in a much better position to take over the responsibilities publishers carry today.Open Access is also often seen as a solution to the 'serials crisis,' a situation where many libraries have been forced to cut journal subscriptions because of price increases. Subscription charges - and the volume of content published - have undisputedly risen more sharply than library budgets. But it is worth questioning to what extent the serials crisis is also due to the level of library budgets – typically around 2% of a university's budget. Some would argue that this level is insufficient in the information age in which we live.

Really? In times when access to information has become so cheap that newspaper empires are crumbling, universities, many of them publicly funded, should pay more for the commodity everyone else is paying less for? That argument takes some more reasoning than just stating it.They cannot be blamed for running their businesses in such a way as to maximise profits.

I agree in principle with this argument, although some people might find the way in which these profits are generated obscene:

Indeed, in recent years the investment made in online and electronic information services could be viewed as balancing out high levels of profits in previous years. Elsevier, for example, has invested at least £45 million in its ScienceDirect service over the past five years, and has also developed the free-to-use science search engine Scirus.

That argument is so ridiculous, one questions the algebraic competence of the author. According to their own reports, Elsevier has posted profits of 3.918 billion EUR over the last 5 years. The 45m pounds (57m EUR) thus constitute a whopping 1.5% of their adjusted operating profits. Now I'm no economist, so I'd really like to know how 1.5% "balance out the profits"?Moreover, although journals can be accessed free of charge under Open Access, publishing these often involves charging authors or their institutions article processing charges.

Again, only if one assumes the Pony Express will keep riding forever.Many critics are dubious of Open Access because they do not believe that the model is economically sustainable, and that, if relied upon, could damage the market as publishing businesses and learned societies experience difficulties due to reduced revenues.

Well, boohoo, what do you think the Pony Express riders or telegraph operators were saying when their end was nigh? In June 2004 Elsevier re-defined its policy on post-prints and institutional repositories: “An author may post his or her version of the final paper on personal web sites and on the institution’s web site (including its institutional repository). Each posting should include the article’s citation and a link to the journal’s home page (or the article’s DOI). The author does not need our permission to do this, but any other posting (i.e. to a repository elsewhere) would require our permission. By “his version” we are referring to a Word or Text file, not a PDF or HTML downloaded from Science Direct – but the author can update the version to reflect changes made during the referencing or editing processes. Elsevier will continue to be the single, definitive archive for the formal published version.”

For one, their policy has now changed to somewhat slightly more idiotic. Second, even if it hadn't, their publicly displayed policy is belied by their attempts to prevent such depositing using the generous 'sponsoring' of lawmakers to introduce bills (the RWA) aimed at preventing such repositories from being filled. Finally, the fact that even if they allow such pre-print deposition, they do so only after an embargo period, reveals that the publishers themselves are not confident they deliver anything of value (i.e., worth paying for). If the publishers themselves have no confidence in their own value, why should we pay them?Open Access, argue critics, does not allow for sufficient investment in technology.

This is such a reversal of fact, it made me lol. Given the very rough estimates of the world-wide academic publishing market with ~12b USD annually in revenue and a fairly accurate estimate of a ~30% profit margin across the main players, there is a potential for 4b USD annual investment in a scholarly communication infrastructure, if libraries would stop spending that money on subscriptions and instead spent the 8b on the publishing costs they'd incur if they published themselves. Compared with the 57m EUR investment by Elsevier, this is roughly a 70-fold increase in investment if universal open access was accomplished by simply cutting out the middlemen.However, publishers and other interested parties have invested significantly in recent years to develop services such as Thomson’s Web of Knowledge or Elsevier’s Scopus which allow access through a single point to content from a range of publishers

Wait a minute: the fact that we have to go to a gazillion different places to find our literature in this year 2012, instead of using a single smart search tool, is supposed to be some sort of accomplishment? In my presentation on this issue, this example is on one of my first slides where I show just how dysfunctional our publishing system is!Capacity for innovation is particularly important in this information age. Market demands from the academic and scientific community are changing and developing alongside the growth of the Internet, and journal publishers are adapting their views of how journal article content fits into the information spectrum. There are now examples of publishers offering more than just the journal content, or bypassing the publication of research results as articles but instead providing citable references within a database.

I guess this is supposed to say that the publishers are now slowly realizing that they should at least offer their users the technology of the early 1990s or all hell will break lose. Well, I for one am not content with 20 year old technology. I want today's technology to assist me in my job and I'm sick and tired of publishers telling me why I have to wait another 20 years before I can even see a preview of it. Scientists have waited patiently for two decades now for publishers to adopt modern technology. I have to say, my patience is worn out. Maybe others are more patient than me.The fact that revenue generated by charging author fees is unlikely to generate the same levels of income that subscriptions have traditionally provided, also creates problems for learned societies, in particular. Profit levels are a major issue for learned societies: a straw poll of ALPSP members in February 2004 revealed that the vast majority of learned societies (87.5% of respondents) generate a surplus from their publishing activities10; this surplus is necessary in order to support these societies’ other, non-revenue generating or loss-making activities.

This is indeed a valid concern learned societies have to face. However, why should the taxpayer care if the learned societies relied on the Pony Express to generate revenue? Should the taxpayer be expected to keep the Pony Express alive only because otherwise the membership fees of those learned societies would have to rise which aren't innovative enough to find other sources of income?It seems reasonable to assume that any system which cannot demonstrate economic sustainability in the long term will not prove successful – at present the Open Access system in not in a position to provide that proof for the satisfaction of the majority.

Who said Open Access needs to be provided by the Pony Express, when we have the railroad?However, scientific publishing is a demonstrably valuable service and one which does not come cheap, particularly in this era of electronic development. Any emerging models will have to be grounded firmly in economic reality to have any chance of success.

The economic realities are that the actual costs of scholarly communication today lie somewhere in the ballpark of 8b annually. And the taxpayers are paying an additional 4b every year for something not even the recipients of these 4b can find any reasons for. I'd like to know why we should keep paying these 4b into the pockets of the publishers' shareholders, instead of investing them in something the public actually benefits from, such as a world-wide public library of science (supported by all the ~10k university libraries in the world) that makes not only the scholarly articles, but also the data itself as well as the software to mine, analyze and visualize these data accessible and sustainably archived for all humankind? I have not found a single sentence in this article explaining what the taxpayer receives from being overcharged 4b every single year. Where are the cons of a public library of science that saves the taxpayers of this planet 4b every year?Posted on Friday 24 August 2012 - 23:03:15 comment: 0

{TAGS}

{TAGS}

Render time: 0.3180 sec, 0.0096 of that for queries.